H |

ow did the Church react to the ousting of the secular aristocracy? First, when asked to support the French revolution, Pope Pius VI roundly condemned it in 1791 in the ironically titled encyclical, Caritas. The condemnation was the opening move by the Vatican against the emerging liberalism, liberty, and equality.

Shortly after the French Revolution, calls began to be heard suggesting that the Church take a leadership role in the cause of liberty. Surely, people said, freedom is consistent with and even lies at the heart of the gospel message and the whole of Sacred Scripture.

Felicité Robert de Lamennais, born prior to the revolution, a scholar, priest and author, engaged a group of followers in this cause. Because there was governmental interference with the Church at every level: governance, education, etc., Lamennais stated that separation of Church and State, complete freedom for the Church, was in the Church’s best interest.

Lamennais and his followers started a daily newspaper, L’Avenir, The Future. Its slogan was "God and Liberty." It subscribed to the full liberating agenda: complete religious liberty, freedom of education, freedom of the press, etc. Lamennais wanted to start a movement based on his belief that this concept of liberalism would find its proper home in the Church. L’Avenir attacked the bishops as blind, worldly and cowardly.

As you might suppose, tremendous opposition arose among the clerical aristocracy to these ideas. The final denunciation came from Pope Gregory XVI in the encyclical Mirari Vos. (1832). In the encyclical he complains that the Church is afflicted with indifferentism. A brief quote says it all: “And so from this rotten source of indifferentism flows that absurd and erroneous opinion, or rather insanity, that liberty of conscience must be claimed and defended for anyone…. Nor can we foresee more joyful omens for religion and the state from the wishes of those who desire that the Church be separated from the State.”

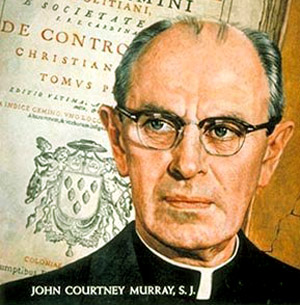

Thanks to the wisdom and efforts of an American Jesuit, John Courtney Murray , insanity made a U-turn and became sanity when the second Vatican Council made plain in its Declaration on Religious Freedom (1965): “In all his activity a man is bound to follow his conscience faithfully…. It follows that he is not to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his conscience. Nor, on the other hand, is he to be restrained from acting in accordance with his conscience, especially in matters religious.” And in the same document: “Government is to assume the safeguard of the religious freedom of all its citizens.”

There we have it: freedom of conscience and separation of church and state. It is just one of many examples down through history where bishops have made a U-turn in their positions on moral issues.

In our next issue, we will look at the bishops’ post-revolution position on equality.

Sources:

The Documents of Vatican II, edited by Walter Abbott, S.J.

The Sources of Catholic Dogma, by Henry Denzinger

Church and Revolution: Catholics in the Struggle for Democracy and Social Justice, by Thomas Bokenkotter.

Sources:

The Documents of Vatican II, edited by Walter Abbott, S.J.

The Sources of Catholic Dogma, by Henry Denzinger

Church and Revolution: Catholics in the Struggle for Democracy and Social Justice, by Thomas Bokenkotter.